Friday, December 29, 2023

Monday, December 25, 2023

Wednesday, December 20, 2023

Separate

They are lonely; the spirit of their writing and conversation is lonely; they repel influences; they shun general society; they incline to shut themselves in their chamber in the house, to live in the country rather than in the town, and to find their tasks and amusements in solitude. Meantime, this retirement does not proceed from any whim on the part of these separators; but if any one will take pains to talk with them, he will find that this part is chosen both from temperament and from principle; with some unwillingness, too, and as a choice of the less of two evils; for these persons are not by nature melancholy, sour, and unsocial, — they are not stockish or brute, — but joyous; susceptible, affectionate; they have even more than others a great wish to be loved. Like the young Mozart, they are rather ready to cry ten times a day, "But are you sure you love me?" . . .

And yet, it seems as if this loneliness, and not this love, would prevail in their circumstance, because of the extravagant demand they make on human nature. . . Talk with a seaman of the hazards to life in his profession, and he will ask you, "Where are the old sailors? do you not see that all are young men?" And we, on this sea of human thought, in like manner inquire, Where are the old idealists? where are they who represented to the last generation that extravagant hope, which a few happy aspirants suggest to ours? In looking at the class of counsel, and power, and wealth, and at the matronage of the land, amidst all the prudence and all the triviality, one asks, Where are they who represented virtue, the invisible and heavenly world, to these? Are they dead, — taken in early ripeness to the gods, — as ancient wisdom foretold their fate? Or did the high idea die out of them, and leave their unperfumed body as its tomb and tablet, announcing to all that the celestial inhabitant, who once gave them beauty, had departed?

Saturday, December 16, 2023

Tuesday, December 12, 2023

Holy Night

"There is such an amazing tragic stillness about her. She never steps out of it, and she never puts it on. It is always there." -- Douglas SirkThe most romantic and tender-hearted Christmas movie I know is Mitchell Leisen's Remember the Night (1940), a storybook comfort written by Preston Sturges in his directorial debut year of The Great McGinty and Christmas in July. A jewel thief (Barbara Stanwyck) is arrested days before Christmas with her trial ~ because of the holiday ~ postponed. Nowhere to go and without money, she's taken by her prosecutor (Assistant DA Fred MacMurray) back home to Indiana, where the girl is also from, to spend the holidays with his family and friends. Back in New York after New Year's, both now in love, he tries to throw the trial -- but she pleads guilty to prevent him from hurting his career. In between is an enchantment road movie, with two detours: a meet-up with a vicious farmer and a small-town hanging judge (whose chambers Stanwyck sets on fire); and a terrifying "reunion" between daughter and mother. Ultimate destination: hope and transcendence and elation.

Curiously hating what Leisen did with the script, but embracing Stanwyck and promising he would write her a great comedy, Sturges would give us the incomparable Lady Eve in 1941. Compared with Eve, the Leisen movie is less smart and less funny (in fact, it isn't a comedy at all), less knowing and brilliant, less artful. Less a work of "genius." For me, however, Remember the Night is the higher and richer work. Perhaps because the culture has turned against what makes the movie great: kindness, forgiveness, redemption, quiet. All of the picture is set in the enthralled emotional key with which The Lady Eve ends; and in the scene where Henry Fonda declares his love for Stanwyck in the moonlight:

Remember the Night (thanks in large part to the great Ted Teztlaff) is all moonlight, with an ending worthy of Dreyer.

At the movie's center is Stanwyck. Our current screen harridans, like the culture producing them, pimp for toughness and "independence" and smarts. Without a whiff of contradiction allowed. Stanwyck, the real deal, never moves without the light of ambivalence shining through. Her voice -- both flat and expressive, both nasal and husky; not the huskiness of booze, debauchery, or a come-on. But tears, fully wept. The voice of someone cried out. And what the guardians of Personhood don't have: a simple, straightforward sincerity; something immovable and deeply reserved; a tension between experience and innocence. It's what gives her her glow -- the agony of consciousness. Here she dwells in the enchantment. And is alienated from it. Yet there's a promise throughout, especially toward the end, that she may break free altogether, to have at last a time purely for her own joy. And ours.

Thursday, December 7, 2023

Sunday, December 3, 2023

Apropos of Nothing

He'd rather lead a band. Who's gonna stop him?

Friday, December 1, 2023

Thursday, November 30, 2023

Wednesday, November 29, 2023

Acceptance, Forgiveness, and Love

Louis Prima. Joe Franklin. Cigarettes. The old. The accented. The poorly dressed. People with scars, moles, jowls, wigs. Bad noses. Bad hair. Delis. Plastic-covered furniture. Howard Johnson's. Colony Records. Lumpy bodies. Cigarettes. S&S cream-cheese cheesecakes and pecan pies. Cherry cheesecake. Heaps of corned beef and pastrami. Blood-soaked, untrimmed steaks. Cigarettes. OTB. Optimo. Cocktail waitresses. Smarm. Ventriloquists. Escape artists. Smiler's. Accordion music. Chain smokers. Dirty grease on groovy hamburgers. Cigarettes. Terrible (but funny) jokes: "I just saw a horrible accident. Two taxi cabs collided. Thirty Scotchmen were killed." The working class. Sweetness. Zest. Enjoyment. Earnestness. Devotion. Joy. The naive and the silly. The human range of New York City. The lost. The lonely and alone. The broken and crippled. Cigarettes.

Vanished. No, not vanished. Banned. From the public, cultural face of the Apple. Gone.

Woody Allen's 1984 valentine to the New York City disappeared is his best and most moving work. And the funniest. His embrace of all we never see anymore -- the shunned -- is keyed to the tune of the true hearts: those who may be talentless and unsophisticated, mediocre and boorish, ugly and uncool. No matter, because all they do is heartfelt and self-forgetful. Toward them here is shown not a moment's camp, condescension, or cruelty. Here, they are celebrated. As are the great stand-ups from the time before Allen hit it big: Corbett Monica, Sandy Baron, Jackie Gayle, Will Jordan -- from places like the Latin Quarter, the Copa, the China Doll. Only caveat: Gordon Willis's inappropriately gloomy photography.

Why not shoot it like this?

Of course, before and after Broadway Danny Rose, Allen's cinema gave / will give a strong push off-stage to the dear hearts. But this is his penance. This is his un-Manhattan.

Wednesday, November 22, 2023

American

"JFK accomplished an Americanization of the world far deeper and more subtle than anything Eisenhower, Nixon, or the Dulles brothers ever dreamed of -- not a world Americanized in the sense of adopting the platitudes and pomposities of 'free enterprise' -- but a world Americanized in the perceptions and rhythms of life. He penetrated the world as jazz penetrated it, as Bogart and Hemingway and Faulkner penetrated it; not the world of the chancelleries but the underground world of fantasy and hope." ~ Senator George McGovern

Tuesday, November 21, 2023

Monday, November 20, 2023

Conspiracy Theorists

Jim Douglass, JFK and the Unspeakable:

One summer weekend in 1962 while out sailing with friends, Kennedy was asked what he thought of Seven Days in May, a best-selling novel that described a military takeover in the United States. JFK said he would read the book and did so that night. The next day Kennedy discussed with his friends the possibililty of their seeing such a coup in the U.S.

"It's possible. It could happen in this country, but the conditions would have to be just right. If, for example, the country had a young President, and he had a Bay of Pigs, there would be a certain uneasiness. Maybe the military would do a little criticizing behind his back, but this would be written off as the usual military dissatisfaction with civilian control. Then if there were another Bay of Pigs, the reaction of the country would be, 'Is he too young and inexperienced?' The military would almost feel it was their patriotic obligation to stand ready to preserve the integrity of the nation, and only God knows just what segment of democracy they would be defending if they overthrew the civilian establisment. Then, if there were a third Bay of Pigs, it could happen. But it won't happen on my watch."

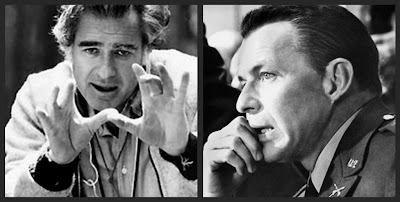

Director John Frankenheimer was encouraged by President Kennedy to film Seven Days in May "as a warning to the republic." Frankenheimer said, "The Pentagon didn't want it done. Kennedy said that when we wanted to shoot at the White House he would conveniently go to Hyannis Port that weekend."The Pentagon need not have worried.

Director John Frankenheimer did complete Fletcher Knebel's Seven Days in May (screenplay by Rod Serling) in the late summer of '63; and his views of the Kennedy White House during the final months of its life haunt the picture and give it an emotional and historical weight it does not deserve. The story is well-known. Air Force Commanding General -- and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff -- James Matoon Scott (Burt Lancaster) plans to overthrow the President of the United States (Fredric March in a manly, beautiful performance, his last starring role) -- a "criminally weak sister" who has just negotiated total and complete disarmament with the Soviet Union. Scott's executive assistant, a man named Jiggs (played in characteristically constipated style by Kirk Douglas), a man who has been cut out of the plot, stumbles across it, reports it to President Jordan Lyman, and after a number of twists and turns -- including the assassination of White House Chief of Staff Paul Gerard (a very effective and furtive Martin Balsam in a too-small role) -- the overthrow is suppressed, the plotters are forced to resign, all the happenings are kept from the childish U.S. public (something the movie endorses), and the Constitution of the United States is preserved.

Boy . . . does John Frankenheimer love the Constitution, and -- as we will see in the previous year's The Manchurian Candidate -- all the established institutions it "preserves and protects." Seven Days opens with the Constitution as backdrop, before giving us the director's vision of the political wars of the early 1960s: the John Birch Society/Minutemen/KKK vs. SANE/SNCC. A brawl breaks out before the gates of the White House. Not to worry. Here come the D.C. police in full riot gear to the rescue.

General Scott's plot is this: kidnap Lyman and hold him incommunicado while taking over all radio and television broadcasting by armed force; then announce on TV and radio the temporary but necessary suspension of civilian authority in order to prevent the military castration of the country. (Scott's plot would later be improved upon by Nixon/Kissinger/David Phillips/Pinochet in the 9/11/73 destruction of Chile.) What is to happen to Lyman? Is he to be assassinated along with other recalcitrant members of the Administration? (The Chief of Staff has just been killed to hide proof of the plot.) What is to be done with public resistance, even if it is merely of the NAACP/SANE/ACLU sort? Scott and the plotters have arranged for the takeover of electronic communications. What about the Washington Post or Time Magazine? ('Though Scott would certainly have had the full support of the Luces.)

Silliness aside, the movie does speak of something real. James Matoon Scott was mostly based on General Edwin Walker, the man stripped by President Kennedy for insubordination and the spreading of fascist propaganda to soldiers under his command. Resigning his rank, Walker in the autumn of '62 led the insurrection against the enrollment of James Meredith at the University of Mississippi, resulting in the deaths of two reporters. Attorney General Robert Kennedy issued a warrant for Walker's arrest on charges of sedition, insurrection, and rebellion. Walker's only response to the warrant, besides having it successfully quashed by a racist Mississippi judge, was to announce his candidacy for Governor of Texas (a race won by John Connally). Walker's last contribution to official history was to be the murder target of Lee Harvey Oswald seven months before Dallas, a Warren Commission canard thought ridiculous by General Walker himself.

Seven Days in May also speaks of how strongly John F. Kennedy had blown away the numbing Eisenhower fog of "cold war consensus" -- leaving him to face the fracturing of the culture formed by that fog and all the new power centers hidden within it, as he tried to guide the society into a quieter and more modest world, one more inward-looking and conscious-stricken. (Perhaps this was what his murderers hated most.)

The movie is beautifully told and paced, trim and clean (but for the bizarre detour taken on Ava Gardner's sad, slatternly performance, nicely introduced by Frankenheimer under "Stella by Starlight"). It also embodies the era's growing obsession with all things public and communal, as seen in its movies: Lilies of the Field, A Child is Waiting, Manchurian Candidate, The Best Man, Dr. Strangelove, Advise and Consent, Fail Safe, The Miracle Worker -- a time when the sight of fruit-salad, generals, admirals, and military bluster caused fear and loathing in the popular culture.

The scenes between Douglas as Jiggs and Ava Gardner -- all her screen time is with him -- are on a different track from everything else: they go nowhere. Gardner's deepening private heartbreak and her skill overcomes Frankenheimer's mere exploitation of her fading beauty and personal distractions (while Douglas just stands around). The movie wastes time on a cul-de-sac concerning compromising love letters written by the married General Scott (as if their exposure would somehow stop the coup) while eliding, beyond March's heartfelt loss over the death of his friend, the assassination of Chief of Staff Gerard. The intentional downing of Paul Gerard's airplane isn't even dealt with, it is merely presumed -- with no effect on future action. And after all, the love letters aren't even used. . .

There was a real-life Jiggs the whistleblower. His name was Abraham Bolden. Bolden was the first black Secret Service agent assigned to Presidential detail, and became a favorite of John F. Kennedy's. Because of complaints made regarding blatant racist treatment, and concerns expressed about sinister attitudes held toward JFK's safety by other WH agents, he was transferred to the Chicago S.S. office in early '62. In late October 1963, Bolden came across evidence of an assassination plot against Kennedy scheduled for November 2nd, during a motorcade from O'Hare Airport to the Army-Air Force football game at Soldier Field. Four men, four high-powered rifles, and a patsy -- working in a building overlooking the President's route. The potential patsy, Thomas Arthur Vallee (an ex-Marine loner with emotional problems), was picked up and held. Two of the snipers were also arrested, then released. The other two escaped the city. Kennedy's Chicago trip was cancelled as in 1963 the country seethed with plots: June '63, Beverly Wilshire Hotel (trip cancelled); November 2nd in Chicago; November 17th in Tampa (motorcade cancelled); Miami, November 19th (trip cancelled); Dallas on the 22nd.

After Kennedy's death, perplexed by the general embrace of the Lone Nut Theory, Abraham Bolden kept speaking to supervisors about the obvious connection between the local plot and what happened three weeks later, and repeatedly requested to testify before the Warren Commission about his Chicago evidence. On May 17, 1964, he directly called J. Lee Rankin, General Counsel to the Commission. On May 18th, Bolden was arrested and charged with fraud, obstruction of justice, and conspiracy, in connection with a black counterfeiting ring. In August 1964, he was convicted on all three counts. Abraham Bolden served three years and nine months in federal prison.

In focusing on a small group of cartoon conspirators vs. a small group of patriots, Seven Days in May ignores -- in the Year of Goldwater -- the rise of Western cowboy economies (space, oil, weapons, big agriculture), ignores the growing nationalist movements across the world, ignores the economic basis of the U.S. war machine, and ignores the ongoing wars within the American deep state itself. A coup launched for purely ideological reasons? Never.

But for a tender version of Iceman Cometh (1973, originally made-for-TV but given theatrical release) starring Lee Marvin, with final roles for Fredric March and the immortal Robert Ryan, Seven Days in May would be the last interesting feature Frankenheimer would make. Although his connection to political murder would carry on. He would host, at his Malibu home, Robert F. Kennedy on his last full night and morning, and drive the Senator to his Ambassador Hotel execution.

Frank Sinatra met John Frankenheimer at a 1960 Hollywood campaign party for Senator John F. Kennedy. Legend has it, Kennedy mentioned (between dances) a book he had just enjoyed, a best-selling political thriller by Richard Condon called The Manchurian Candidate.

The director's work prior to the party consisted of almost 200 (mainly social issue) television dramas. In 1960, godfathered by Burt Lancaster, Frankenheimer was given his first shot at a full-blown feature (a forgettable independent called The Young Stranger came-and-went in 1957): The Young Savages, starring Lancaster in a sort of black-and-white version of West Side Story without the songs. During Savages, Frankenheimer and producer George Axelrod (screenwriter of Breakfast at Tiffany's) bought the rights to the JFK-endorsed Condon novel, a project already rejected by several studios. In early '61, they grabbed the interest of Sinatra and the movie went into production one year later.

The Manchurian Candidate would not be the first instance Frank Sinatra dove into assassination waters. Toward the end of his tortured, hopeless husband-love for Ava Gardner, before his Hollywood-career saving Oscar for From Here to Eternity, he contracted to play in Lewis Allen's Suddenly (1954) -- an inert, pointless movie made twice interesting: it is a movie the Warren Commission claims was TV-viewed by Lee Harvey Oswald shortly before Dallas; and Sinatra's raw, almost-hysterical performance as an Army section-eight turned mob-hired presidential assassin.

If The Manchurian Candidate has too much politics (or not enough of the right sort), Suddenly has none. Johnny Baron (Sinatra) doesn't know who is paying him $500,000 to kill Ike. And doesn't care. (My money is on Nixon and the Dulles Bros.)

Johnny summarizes the story's POV:

The great Sterling Hayden, fresh off Johnny Guitar, plays a small-town California sheriff and is totally wasted. The whole movie feels post-dubbed; and has a McCarthyesque love of police authority. Sinatra doesn't appear until 20 minutes into a 73-minute movie, but when he does he blows a hole in the screen. We are now used to seeing strung-out military-trained psychopaths performing blowback when returned to families and country, as movie characters. Hardly at all in the Fifties, and Sinatra's in Suddenly is the most frightening. (The way he yells "It didn't stop!") Career desperation or not, what other star in that time would have signed on to play such a repulsive character?

How Ava deepened his talent; and his soul. . .

Frankenheimer's style in The Manchurian Candidate is as baroque and wet as his style in Seven Days is flat and officious. Yet the two works have much in common: worship of a behaving military and its honor; a 6th-grade history book's presentation of how power works; a classical conservative's faith in how it should; embrace of all existing institutions (lone exception, MC's Republican Party, not exactly a career-breaker in 1962); media power absent; so, of course, is capitalism. The two movies' decapitation plots are like Potemkin villages. In Seven Days the cadre of generals exist apart from national and state law-enforcement, from international support, from banking or other financial hierarchies. The word "corporation" is not used in either film. The intelligence community does not exist. (Did James Angleton secretly bankroll Frankenheimer as means of distraction?) Manchurian Candidate's plot is a Bircher nightmare, only worse. Here even the most virulent of the far right are Sino-Soviet front men and women. When Angela Landsbury (great ~ Sinatra wanted Lucille Ball for the part!) reveals to her son Raymond Shaw (Laurence Harvey) the final piece of the plot, she announces her intention to betray her Communist sponsors. How? For what purpose? For whose benefit? Raymond's? We see no plans made for his escape after assassinating drip candidate Benjamin K. Arthur. She says she will create the most vicious and bitchiest police state of all time. Again, how? By a Russian/Chinese land invasion? (The Sino-Soviet split was already obvious by '62.) Then Frankenheimer blows the scene with that stupid mommie-kiss.

In the screenplay adaptation, it's clear Frankenheimer and Axelrod hoped to push the more mythomaniacal and (worse) Freudian aspects of the Condon novel to comic book levels. All hopes crushed by Frank Sinatra's brave, naked, deeply-wounded performance.

Inside the thick political shell of the movie there exists two worlds elsewhere: Josie (Leslie Parrish) and Raymond; Rosie (Janet Leigh) and Major Marco. Here the work's obsession with ideology and plots quiets and ends. And briefly, it embraces a Borzagian world apart from the power-saturated universe. Perhaps the strangest and most unsettling parts of Manchurian Candidate are the flashback sequences with Raymond and Josie, and her dad Senator Thomas Jordan (John McGiver, stealing every scene he's in). For Raymond and the father seem irremediably gay. Nowhere to be found in the Condon book, the gayness extends to Raymond's first boss (and domestic victim) Hobart Gaines and his very fruity bedroom, and to the star-chamber scenes in Korea. (Similar to the torture in Michael Cimino's reactionary and stupid The Deer Hunter, in MC the facts are turned upside-down. The U.S. military and its puppet SVN army used tiger-cages for torture. The U.S. government in the 1950s -- the movie is set in the 1954-56 period -- created brainwashed/torture/assassination victims via Allen Dulles-sponsored programs such as MK Ultra.) And let's not forget the Red Queen. . .

With Raymond Shaw, Frankenheimer and Axelrod have added to Norman Bates of two years before in creating a new American type: the sexually-frustrated loner whose only real orgasms are acts of violence. Shaw could be Bates with a Cambridge polish and an alive mother. It was just the beginning: Oswald, Speck, Ray, Sirhan, Bremer, Hinkley, Manson, Whitman. All ostensible loners, all with sinister intelligence connections.

Frankenheimer is so successful with the brief scenes of Rosie and Ben Marco he almost capsizes the film. (Perhaps the half-hour cut after disappointing previews contained much more of the couple.) They exist in a different movie. (Days of Wine and Roses or perhaps Axelrod's Breakfast at Tiffany's.) We only get a taste which leaves a serious question: What draws her to this clearly sick and broken man? Has Rosie been sent to cover Ben, as Eva Marie Saint covers Cary Grant in North by Northwest? And let's hear it for Janet Leigh, such a talented gal who was indispensable to some of the key works of her time: Candidate, The Naked Spur, Touch of Evil, Psycho.

The Manchurian Candidate was a box-office bomb and -- along with Suddenly -- removed from circulation after 11/22/63. Seven Days in May was scheduled for an early-December '63 release, postponed until the following February with the planned ad-campaign and nation-wide showings trashed. (It only opened in select theaters in select big cities. None in Texas.) It was also taken out of circulation until around the time of Watergate. Both films are in an honorable and classical tradition of liberal filmmaking as vanished as the Hollywood Palace. (The only modern equivalent I can think of is Clooney's Good Night, and Good Luck [2005], a fine chamber piece whose sole theme seems to be: people should treat each other decently.)

While Seven Days in May made its final pre-release adjustments, and The Manchurian Candidate disappeared after completing its theatrical run, David Atlee Phillips, Richard Helms, General Curtis Lemay, Admiral Arleigh Burke, Allen Dulles, Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge, Des FitzGerald, Tracy Barnes, Jim Angleton and others murdered John F. Kennedy. Two days later, his accused assassin was killed on national television. On Novermber 25, 1963, Kennedy was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. On the 26th, Frank Sinatra, George Axelrod, producers Howard Koch and Edward Lewis, Rod Serling, Burt Lancaster, and John Frankenheimer all went back to work.

Sunday, November 19, 2023

Let It Bleed

Part Manchurian Candidate, part Sci-Fi, part detective story, "The Inheritors" is pure Kennedy Culture. (And a great example of what Mad Men is not -- a show about as cold and plastic and ordinary as Barack Obama's heart.) Intentionally scheduled by Outer Limits creators in honor of the one-year anniversary of Dallas, this is a heart that bleeds.

Four Vietnam combat soldiers miraculously survive bullets to the brain; subsequently, they embark on a shared mission which controls and confuses them, and arouses the hostile suspicions of government agents. Eventually the soldiers and agents discover that the mission involves kidnapping children, and only at the end do they discover its next step.

The Other as evil vs. the Other as not other: a driven visionary collective of men attempting something risky and noble, while paranoid Feds hound and revile them, suspecting only the worst in their motives, actions, and results.

As Fed Robert Duvall masticates the scenery, the great Steve Ihnat steals it as Lieutenant Minns.

The ending.

Saturday, November 18, 2023

Acquainted with the Night

John F. Kennedy's tribute to Robert Frost, Amherst College, October 26, 1963. He was speaking of Frost, but also -- as we now can feel -- about himself as well.

How far we have traveled away from both men's dreams.

Thursday, November 16, 2023

Ten plus One (minus two)

We're told there are over 10,000 books, mostly or wholly, about the assassination of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy registered with the United States Library of Congress. Most are chum, illiterate or self-serving, off the point or below it, corrupt and venal, distracting or downright conspiratorial.

These are, in my opinion, the best eleven (with a coda). Meagher is the best place to start.

Accessories After the Fact (1967) by Sylvia Meagher

She was the first and remains in many ways the best and most comprehensive. Her fury at the flagrancy and incompetence (for this was an incompetent whitewash) of the Warren/Dulles/Hoover/LBJ cover-up -- and toward the whore mass media, a Sixties media whose bondage to Power was much weaker than our own -- burns through every page. Unlike most authors (good and swill) attracted to this topic, Meagher is a beautiful writer; and a great detective. Perhaps her best chapter is on the concoction known as the murder of Dallas police officer J.D. Tippit. Not only does Meagher prove accused cop-killer Lee Harvey Oswald innocent, since not at the scene, but that Tippit's very strange movements before and after the assassination suggest that J.D. may have been offed by one of his own. A masterpiece getting more masterful through time, even though written only two years after release of the Warren Report and its 26 volumes of non-supporting evidence.

Six Seconds in Dallas (1967) by Dr. Josiah Thompson

The perfect early-stage companion to Meagher. Dispassionate and architectonic, Josiah Thompson takes us as far as anyone has toward knowing the (because of massive corruption and destruction of evidence and witnesses) unknowable: when and from where the Dealey Plaza shots came. With immense photographic and artwork detail, Six Seconds in Dallas proves the two shots from the front, one to JFK's throat, the other to his right temple; two shots from the rear, one to Kennedy's upper back, the second to the top right of his skull; a missed shot from behind, flying over the limousine, hitting a curbstone, and causing a chip which injured bystander James Tague; and a shot from behind traveling through Texas Governor John Connally (and unfortunately not killing him). Here, the Magic Bullet Theory is destroyed. The Single Bullet Theory is destroyed. And so is the Warren Commission's nonsensical time sequence. Thompson's amazing work was accomplished without access to a moving Zapruder film, the autopsy photos, or the Dallas police dictabelt recording of the shooting.

Conspiracy (1980) by Anthony Summers

The first major book written on the case after public release of the Z-film and the dreadful autopsy materials, and after completion of the post-Watergate investigations (the Rockefeller Commission, the Pike Committee, the Church Committee, the House Select Committee on Assassinations). Itself, it is a magnificent piece of investigative journalism, a trove of leads. Summers makes available to the general public for the first time: Rose Cheramie; the witnesses to the strange incident at Clinton, Louisiana during the summer of '63; Lee Oswald working for Guy Bannister; David Atlee Phillips and David Morales; Oswald's curious route through Finland on his way to his Soviet "defection"; the impersonating of Oswald in Mexico City; the fake Secret Service agents behind the grassy knoll fence immediately after the shooting. Here, an Irish-born journalist does what no U.S. journalist dared to do, what no U.S. journalist would permit any colleague to even begin. However, one must emphasize the 1980 edition of the work. For tragically, Anthony Summers turned tail and became just another greasy pole climber, just another condescending defamer of serious researchers who reject the Lone Nut fairy tale. First in a 1994 eviscerating "update" of Conspiracy, now named (nonsensically) Not in Your Lifetime -- Summers climbing aboard the hate Oliver Stone / love Gerald Posner media gravy train. And last month Summers did it again, with a second downgrading "revision" -- again with the nitwit Not in Your Lifetime title -- in which he runs headlong into the dear arms of the Obamian corporate / media police state by bravely dumping on his own original research, on long-dead Jim Garrison, on long-irrelevant Mark Lane, on the ignored Joan Mellen, and on everyone else who has anything to do with anti-Establishment action or thought. No rebel he, is sniffy Summers. Anthony Summers, he dead. Conspiracy (1980) lives on.

On the Trail of the Assassins (1988) by Jim Garrison

The great American patriot and district attorney tells of his breaking of the case, of his trial and investigative innocence and incompetence, of his own destruction by FBI, CIA, Johnson Administration, Senator Robert F. Kennedy and his aides, television and newspaper media, and the cracker establishment of Louisiana. Garrison was not only a great patriot, but an elegant writer and storyteller. And a very funny man.

Spy Saga (1990) by Philip Melanson

A micro-view of the assassination. Actually, not about the assassination at all. Philip Melanson takes the dribs and drabs given to us by U.S. intelligence and law enforcement agencies, fills in many gaps through his own sleuthing and forensic genius, and gives us a Lee Harvey Oswald as an operative who was never really allowed to come in from the cold. Under Melanson, Oswald was recruited by military intelligence while in the Pacific as a Marine (perhaps even earlier courtesy of Civil Air Patrol leader David Ferrie), taught Russian at CIA's Monterey School of Languages, sent to the Soviet Union in 1959 as a false defector, brought back to the States (now with a Russian wife) in '62, and used as a "dangle" in up to a half-dozen covert ops in Texas, Louisiana, and Mexico City (mail order gun sales, anti- and pro-Castro infiltration, voter registration drives, Communist Party USA) until his ultimate dangling in Dealey Plaza on 11/22/63. An astonishing read of very scanty (and withheld and destroyed) evidence.

Deep Politics and the Death of JFK (1993) by Peter Dale Scott

Looking through the other end of the telescope from Phil Melanson, our greatest political historian maps Dallas with a macro-coverage, using much the same method: Scott links small pieces of evidence through an economic, political, and criminal labyrinth most of us could not begin to fathom; for what we are used to seeing, trained to see from birth, is the public state, the public economy, and a concept of crime embraced by everything from Batman to Dragnet, from Columbo to The Wire. What Scott brings to life here is what he calls the Deep State, a malignancy which was nascent throughout the 1940s and 1950s, what was fully born on 11/22/63, and what has since swallowed the public state whole: a parallel international secret power system, composed of mafias, private corporations, military cadres, intelligence and security and police apparatus; financed by drugs, stolen government dollars (the 2008 "bank bailout" being the largest and most historic example), corporate funding; engaging in illicit violence to protect the status and interests of the powerful. In Deep Politics and the Death of JFK, Dallas is the template, a template which since '63 has suffocated us all. Honore de Balzac was the greatest of all conspiracy theorists. Among modern English language historians, Peter Dale Scott comes the closest to him. A dense, sometimes opaque book not for the faint-hearted.

The Last Investigation (1993) by Gaeton Fonzi

Alas, it would be so. Gaeton Fonzi was lead investigator for the hopeful, degraded, hijacked, yet still valuable House Select Committee on Assassinations (1976-79), a committee whose final report would point to more than one shooter firing at the Dallas motorcade. Under enormously difficult conditions -- funding cut by Congressional reactionaries and intelligence stooges; blasphemed by the press; cut-off at the knees by feuding staffers (some of whom were double agents) -- Fonzi was a miner finding much golden ore. It was he who discovered the key witness (Antonio Veciana) linking patsy Oswald to Kennedy assassination ringleader David Atlee Phillips; linking Phillips to CIA / JMWAVE Miami station chief David Sanchez Morales (Morales would also participate in the CIA execution of Che Guevara in Bolivia four years after Dallas, a fascist murderer for all seasons); Fonzi would nail George DeMohrenschildt, Oswald's Texas handler, to the wall, until DeMohrenschildt's untimely death, the day before a crucial interview with Fonzi. For it is death which destroyed the Last Investigation. Beyond DeMohrenschildt, there are the murders of Jimmy Hoffa, Sam Giancana, John Rosselli, top FBI administrator William C. Sullivan (supposedly shot when someone mistook him for a deer), Rolando Masferrer, Charles Nicoletti, Carlos Prio, Sheffield Edwards, William Harvey, David Morales, William Pawley, Thomas Karamessines, John Paisley: all murdered during HSCA's time, rivers of mid-70s blood, the glue holding together the fetid deep state system while it tottered. And my how it worked, leading to the Reagan Restoration -- and beyond. But not only blood. As Gaeton Fonzi tells it, one man castrated the HSCA from within: corrupt legal bagman, and Chief Counsel, G. Robert Blakey. It was Blakey who made sure all pointed toward Oswald, or the Mob (same distraction); all pointed away from CIA. Richard Sprague -- lion-hearted, unimpeachable, incorruptible, fearless Philadelphia D.A. Richard Sprague and his Chief Investigator Bob Tannenbaum were originally put in charge, before Blakey. Sprague was character assassinated by the intelligence media, then fired. Tannenbaum quit. Leaving the HSCA to the stinking fixer Blakey. Gaeton Fonzi, a blessing, a hero, stayed on, giving us this brave, grand book.

Breach of Trust (2005) by Gerald McKnight

Professor McKnight's inside/outside investigative history is the first major work of the new century and it is the finest picture we have of what the Warren Commission truly was: a funnel for every piece of distortion, misrepresentation, false witness, suppressed witness, crime lab fakery, photographic fakery, autopsy fakery, ballistics fakery, Ivy League shyster and cover-up artist, ideological distortion, personality distraction, and psychobabble necessary to paint the Lone Nut fairy tale portrait -- composed, perhaps most disturbing, against a faux mournful tribute to the late President. McKnight makes clear: three men ran the Oswald Star Chamber, none of them named Warren: Kennedy assassin Allen Dulles, accessory-after-the-fact J. Edgar Hoover, and chief beneficiary of the crime Lyndon Baines Johnson. This is our J'Accuse!

Brothers (2006) by David Talbot

The most beautifully written, most passionate, and probably the saddest of all the books in the canon; rejecting all irony, camp, narcissism, deconstructionism, moral relativism, nihilism, sexual prurience and other malignancies of our time. John and Robert Kennedy were heroes. They were murdered by evil men. End of story. Talbot takes the top off the cesspool of enemies who brought down the US Government in 1963 and murdered the leading Presidential candidate of 1968. Who were the enemies? Sex haters, race haters, America-Firsters, oil junkies, mob guys, fascist intelligence agents, military dictators, tweed-covered garbage such as Dick Helms and Des FitzGerald, right-wing publishers and editors, drug executioners, psychopathic politicians, Goldwaterites. And that's the horror of the book. Fifty years later, what is left on a popular or establishment level of the idea that society and government must be judged by the way the weakest and most vulnerable among us are taken care of? The answer is: nothing. There is nothing left of that. Which is why the sense of doom and sorrow one takes from Brothers will be long lasting. The worst of our history murdered the best and got away with it. Scott free. Not only did they get away with it, but they've created the sort of society diametrically opposed to everything JFK and RFK stood for: a country where the least human and most nakedly aggressive dominate everything. This was the newer world others' sought. Born from the gore of Dealey Plaza, they've achieved it. For a bracing and deeply moving reminder of what was lost, one cannot do better than David Talbot's magnificent book.

JFK and the Unspeakable (2007) by James Douglass

If Talbot's Brothers is a tributary hymn-of-despair, Jim Douglass's JFK and the Unspeakable is also a hymn, in a way a companion piece to the Talbot book. But Douglass's sound is a hymn of belief, hope, and transcendence. In Kennedy's murder by the forces of the Unspeakable, a contemporary crucifixion, Douglass sees meaning beyond the resulting Vietnam genocide, beyond the takeover of our society by back-stabbers, soul-crushers and ghouls, beyond the shifting of cultural meaning toward something hideously empty and narcissistic -- meaning in the symbol of a man willing to die for his beliefs, for his (in Douglass's term) "turning." One can argue with this, for at the heart of Douglass's profoundly spiritual argument, there is something anti-political. Rather than view John Kennedy's murder as a political and economic act by men who saw themselves only in those terms, we experience it through Douglass's writing as a modern day Stations of the Cross. First Station: Kennedy refuses war with Laos. Second Station: Kennedy refuses invasion and air attacks during the Bay of Pigs; Third Station: Berlin Wall goes up, Kennedy lets it stand. Etc. It is an agony, as we follow Kennedy's turning and his movement toward the Golgotha of Dallas. So what do we do? Much can be said for acceptance and a belief in transcendence, a belief in Grace. But as Jack Kennedy said: "Here on earth, God's work must truly be our own." Do we let this crucifixion stand? Do we accept the vampires now in almost total control? Do we take up arms against a sea of troubles and by opposing end them? Can they ever be ended here on earth? Do we let Catholicism be defined by Hitler-Jugend Joseph Ratzinger and his successor, men who led the war against Liberation Theology? Do we let Christianity be defined by Tim LaHaye and his life-haters? Such questions. That JFK and the Unspeakable forces us to ask them marks the Douglass book as a rare and beautiful masterpiece, one to go back to many times through the years.

Into the Nightmare (2013) by Joseph McBride

Amid the cascade of assassination books covering us this 50th Anniversary season, Joe McBride's is the best. This journey by one of our great film critics (works on Hawks, Ford, Capra, Spielberg, several on Welles) begins with his role as a 12-year-old volunteer during JFK's run in the 1960 Wisconsin Democratic primary. (Kennedy's state chairman was McBride's mother.) We follow the author through the agony of Dallas, his belief -- as a patriotic anti-Communist Irish-Catholic teenager -- in the bona fides of the Warren Report, his transformations -- via Vietnam, race riots, the murders of Malcolm / King / RFK, and Watergate -- into something very different, to his search for the truth of the day (as Norman Mailer wrote) the post-modern world was born. And what a start to the search: it was McBride in a 1988 Nation magazine piece who exposed then Vice President George H.W. Bush, then running against sap Michael Dukakis, as a CIA enforcer from way back, beginning in the late-1950s, and who was up to his preppie neck in the Texas intrigues of November '63. The most valuable and astonishing parts of Into the Nightmare are the very fresh and convincing sections concerning officer J.D. Tippit. Rather than the unknowable dumb cop who just happened to get in homicidal Marxist maniac Lee Harvey Oswald's way during his escape from Dealey Plaza, Joe McBride makes Jefferson Davis Tippit well known: as part of the plot to kill Kennedy, Tippit's role was to track down Oswald immediately after the ambush and gun him down, before arrest, before Oswald had any chance to declare himself a patsy. He also suggests that Tippit -- a crack shot -- may have been one of the gunmen in Dealey Plaza. A beautiful and stunning book, with rare photographs, streets maps, and analysis.

Vince Bugliosi's Reclaiming History is a 3,000 page monument to True Believing in Official Fairy Tales. Unlike 90% of Reclaiming History commentators, I've actually read all 1,700 text pages, 1,000 pages of endnotes (outstanding endnotes), hundreds of source note pages, plus two photo sections. You must hand it to Mr. Bugliosi: he is the Joan of Arc of this event. Regardless of POV -- and of course his POV is to basically suffocate and de-mystify the mysterious -- one cannot but admire his passion and hard work. And, he is a very funny writer. His various descriptions of Oswald the Cheapskate, Oswald the Potential Jet Hijacker ("jumping around the house in his underwear, preparing athletically for the hijacking, only caused baby June to think he was playing with her"), Marina the Sex Maniac, Marguerite the Harpie (and the Sex Maniac). His best humor (and his nastiest spite) is left for the real chuckleheads in the research community: the pathetic Robert Groden, the hapless photo expert Jack White, Mark Lane's endless self-promotion etc. But the fatal problem with the book is its boy scout level worship of everything official. Bugliosi discredits most everything he writes because from early on we see that his prism is exactly what one would expect from an establishment-based former D.A. So the book is a valentine to the honor of Gerald Ford, Earl Warren, Allen Dulles, David Belin, Arlen Specter, Henry Wade(!), Jesse Curry, Will Fritz, J.Edgar Hoover(!!), every member of the Dallas Police Department (except Roger Craig), every member of the FBI, every member of the Clark Panel/Rockefeller Commission/HSCA/ARRB, every member of the Secret Service (except Abraham Bolden), every member of the mainstream media circa 1963-64, the Bethesda autopsy doctors, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Dick Helms and James Angleton, those fine patriots David Phillips, David Morales, and Guy Bannister, plus every official crime lab Vince could think of. How touching. (Or as Vinnie would write, "my, my.") My-my indeed. What sort of world does Bugliosi live in? Are we really supposed to take on faith -- which is what one must do to accept much of the evidence he provides -- the honor of people involved in investigating such a history-changing event? Yes, we are. There must be a 1,000 instances in the text and endnotes along the lines of: "What kind of loonie-bird could believe [fill-in-the-blank] would jeopardize his life/career/reputation/freedom by covering up murder?" Well, where do we start? Sadly, the history of the world is one long continuing account of people in power doing exactly that in order to remain in power, exactly to keep their reputations/freedoms/careers. If a bunch of cheap Ivy League (and oh my how VB loves the Ivy League!) legal hustlers trying to make their bones are faced with the challenge of covering up a crime which if exposed would crack in two the very establishment they wish to enter and dominate, and if there is already plenty of proof that being offered that gig and turning it down for some kind of pusillanimous and righteous reason may lead to harmful effects (Ruby/Oswald being Exhibit A), the really confusing and naive conclusion would be to assume the hustlers would not grab for the brass ring. And to assume some sort of holy righteousness on the part of the apparatchiks who made up the Warren Commission, a personal morality that would lead John McCloy to stand up and say "Hey, Mr. Chief Justice. This stinks. And the odor is coming from my pal James Angleton's death-squad offices down at Langley, and from our Mexico City Station" -- to quote the great philosopher Michael Corleone: "Who's being naive, Vince?" If only the world and the powerful were that way. We know they are not. And surely former D.A. Bugliosi knows they are not. So one wonders what private ghosts he is trying to exorcise with this book. He's a brilliant man with a great sense of humor -- he can't possibly believe in the automatic honor of these people, can he? Is he trying to convince himself in a late stage of life that everything he did in service to establishment power was not so much sound and fury, signifying nothing? Is Mr. Bugliosi trying to make up for not becoming a revolutionary? Is he trying to avoid the same feeling Dave "Maurice Bishop" Phillips felt on his death bed, when he confessed to his estranged brother that "Yes" he was in Dallas on 11/22/63? -- the kind of feeling one gets when one looks toward eternity? I believe Mr. Bugliosi is -- unlike practically all members of great power elites -- an honorable man. There is no way someone creates this sort of work for the money. And it is heroic how far he went with his obsession. (In medieval times, like his role model Joan of Arc, he would've been burned at the stake.) An honorable book, however deranged.

No honor in the other, more typical, keystone. For it is something normally found in a dung heap. For thirty years, Norman Kingsley Mailer blew the trumpet of JFK assassination conspiracy, generally pointing his noise toward CIA, the military, and LBJ. As the 80s turned to the 90s, as Jim Garrison and Oliver Stone commandeered the discussions concerning how Power in America really works, and as Mailer married his 8th wife while his 7 previous brides were suing him for back alimony (half of whom he may have stabbed), this once-great, bravery-obsessed writer took on a pimp job offered up by Random House editor-in-chief and Reichsmarschall of the Culturally Depraved Sir Harold Evans. (Evans's immediately preceding hire was of some plagiarizing Botox-patient by the name of Gerald Posner.) Mailer's assignment turned into something called Oswald's Tale, which should have been called Mailer's Tail since the book is almost 700 pages of Norman Kingsley taking it up the bum from Warren Commission liars, U.S. fascist intelligence sources of all flavors, pathetic psycho-babble about Oswald's probable homosexuality (hence his need to shoot the virile JFK from behind), marriage counselor guidance, and "newly released" KGB forgeries concocted by Boris Yeltsin's mafia goons. For decades Mailer lived off the pose of being the most courageous dude -- and certainly most courageous writer -- in America: the Miller / Mailer / Manson man, Gore Vidal would call it. "God is not love. God is courage. And love is the reward." So it went. That we're all born with a cancer-gun inside us. That we're all faced with a moment when that gun is cocked, when we must choose between bravery and fear. If we fail to be heroic, the gun goes off. Cancer = cowardice. Norman Mailer lived for a dozen years after writing what surely is one of the most venal and corrupt books ever coming from a major writer. And it seems he did not die of cancer. Yet the cowardice contained within Oswald's Tale resounds with the force of an atomic blast.

Wednesday, November 15, 2023

Tuesday, November 14, 2023

Sunday, November 12, 2023

End the Chosen

Saturday, November 4, 2023

Thursday, November 2, 2023

Wednesday, November 1, 2023

Tuesday, October 31, 2023

Sunday, October 29, 2023

Saturday, October 28, 2023

Near Dark

October 1963 ~ on the cusp of the Unspeakable. World Series Game One: the L.A. Dodgers (BOO!) vs. the New York Yankees (BOO!!), Sandy Koufax vs. Whitey Ford, Ernie Harwell and Joe Garagiola, funny and sweet radio spots, lots of smoking and drinking and lots more good cheer.

They've been saying around here that Camelot was a myth. The heck it was.

Friday, October 27, 2023

Heroes and Pigs

Thursday, October 26, 2023

Kristallnacht??

Wednesday, October 25, 2023

Monday, October 23, 2023

Sunday, October 22, 2023

Thursday, October 19, 2023

Tuesday, October 17, 2023

Tuesday, October 10, 2023

Monday, October 9, 2023

Friday, October 6, 2023

Are You an Acceptable?

Tuesday, October 3, 2023

Sunday, October 1, 2023

October

If one would ask how the monumental can be tender, October in New York City is still the answer. The city then recalls us to the brutal and to the awesome. Her wood and asphalt and brick skin becomes luminous in any pale light ~ it also reflects the shadow of the rock: New York in such shadow on a sunny day, the glass of her eyes has the blue of the sea. Days and nights slow down, people seem readier to recognize others, before the Transfiguration of Christmas.

New York October, when the magnificent blue sky glows like sapphire, after the sun sets. Streams and ponds and lakes of water flash blue. Great lines of silver-grey poplars rise and make avenues ~ or airy grey quadrangles ~ across the Park, their top boughs spangled with gold-and-green leaf. Sometimes gold-and-red, a patterning. A bigness ~ and nothing to restrain the romantic spirit. . .

Monday, September 18, 2023

Tuesday, September 5, 2023

The 21st-Century US "Left"

"To be ultra is to go beyond. It is to attack the sceptre in the name of the throne, and the mitre in the name of the altar; it is to maltreat the thing you support; it is to kick in the traces; it is to cavil at the stake for under-cooking heretics; it is to reproach the idol with a lack of idolatry; it is to insult by excess of respect; it is to find in the pope too little papistry, in the king too little royalty, and too much light in the night; it is to be dissatisfied with the albatross, with snow, with the swan, and the lily in the name of whiteness; it is to be the partisan of things to the point of becoming their enemy; it is to be so very pro, that you are con."

-- Victor Hugo, Les Miserables

Monday, September 4, 2023

Wednesday, August 30, 2023

Between Sorrow and the Shadow

Mouchette (1967) and Au hasard Balthazar (1966) are the two darkest, and most Catholic, great films ever made. In both works, innocents -- a girl and a donkey -- suffer their own Stations of the Cross -- beaten, raped, whipped, abandoned, slapped, burned -- and then die. Both works are anthologies of sadism, ending in moments of Transfiguration; one in a pond, the other on a hillside; both to pieces of sacred music. However, little is divine. We're faced with a hard, physical world of muddy fields and of things and objects; and forces of control and imprisonment. Director Robert Bresson's double miracle turns a suffocating austerity into endless plenty; so oblique and concentrated are Mouchette and Balthazar, they become the walls of a collapsing hell. And then home.

Bresson was interviewed in late 1966, between the making of the two movies.

Thursday, August 24, 2023

Light

She always refused to think in terms of "rights," thinking only of "obligations." And to think of her from where we all now stand is to feel nothing but shame, guilt, and darkness.

The great John Berger reads from her poem "Chance."

Sunday, August 20, 2023

Thursday, August 17, 2023

Tuesday, August 15, 2023

Be Afraid

David Cronenberg's The Fly premiered almost forty years ago this month and seems to have been largely forgotten. (While other US movies from the period continue to receive attention and accolades -- Hannah and Her Sisters, Platoon, Back to the Future, After Hours, friggin' Blue Velvet.) Upon release it was generally (Kael, for once, got it right) dismissed as just another Hi-Tech remake and gross-out movie. It is instead one of the great works of the 1980s, a movie about separation and loneliness, fear of love and sex, fear of communion and hope. It is about Reaganism and what the 1980s did to our emotional culture. Consciously or not (we know Cronenberg's father died during production of a terrible cancer), the director seems to have sensed that we were taking a turn, that our hearts we're growing quieter, something of the best in human life was now going away forever; that what was public and communal would now be forced back into the darkness of privacy; from now on we would have to look more inward for satisfaction and understanding, through imposed hatred of all things public and the increased dominance of technology. Very hard to watch, it is a movie of overwhelming pain and sorrow and loss, with only three major speaking-parts in its almost 100 minutes.

Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum) is a genius scientist who works and lives in a warehouse on the dark side of the moon, his only companions being his lab animals. At a science convention Brundle meets a magazine reporter (Geena Davis, Goldman’s soon-to-be-wife of three years) who takes up the goofy and earnest man’s invitation to see something which will “change the world as we know it.” Indeed. And Ronnie (the reporter) hands over one of her silk stockings after flashing a gorgeous leg right after arriving at his warehouse. Her first stance toward him, however, is a rather knowing condescension – until he demonstrates what will change their worlds: he “teleports” the silk stocking from one “telepod” to another (initially she calls them “designer phone booths”). She rushes back to her magazine’s editor-in-chief, a typical prick mediocrity perfectly played by John Getz. Seth is outraged and he convinces her (and the editor) to wait. He offers to bring her with him, step-by-step, until he and his travel/space revolution is ready to launch; and in hopes she will along the way fall in love with him. She does. Almost from the moment she does, he (literally) begins to fall apart. And the rich red aroma of sorrow – embraced by Howard Shore’s Grunenwald-like score and captured by DP Mark Irwin’s Tintoretto darkness – descends like a mourning veil.

Brundle is a man who wants nothing more than to love, to be part of something other than his own mind. Something not in his nature, or destiny, for him to have. He follows his self-destruction and lonely descent into hell with purity and courage. He does not fight it. It is all he really knows. After successfully teleporting a lovely baboon (his first attempt was not successful), Ronnie suddenly leaves him – to finally rid herself of the prick boss/ex-boyfriend. Within moments of her leaving, Seth begins to fade, feel insecure, jealous and possessive. He drinks, gets quickly drunk, and in a stupor decides to teleport himself before the pods are ready. Successfully he believes.

Ronnie returns to him and they fall. At first, she makes him feel like a sexual superman. When we next see the couple in public, Seth is in full Yuppie regalia, turned into a would-be Don Johnson. He's now rocketing and she cannot keep up, she is too sexually square for this once and future shut-in. So he dumps her, after degrading her. “I don’t need you anymore! Never come back here!” He decides to prowl the streets and kick some Gentrification City ass. (Literally Toronto but a stand-in for Portland or Seattle or Park Slope or some other pseudo-hipster shithole). After breaking an arm or two in half, he feels like the toughest stud in town.

Apart from Ronnie, the descent is fast, as he quickly becomes as physically repulsive as he must have feared he was his whole life. After a month, he asks her to return. He has been turned – like the failed attempt with the first baboon – inside/out, his fear and self-loathing now exposed for her to see. She has no choice but to turn away.

She shakes her head. But soon, Ronnie will plead with Getz to arrange an immediate abortion, words Seth will hear:

Penultimately, she is to kill his baby. Finally, he commits suicide by begging his loved one to murder him.

He also instructs her about Insect Politics:

A perfect description of our post-Reagan world, and never so anthropodic as in 2023.

Only three characters speak for the movie’s first 50 minutes. (Five minor roles later include Cronenberg as Ronnie’s gynecologist, and a very nice and sexy turn by Joy Boushel as Seth’s bar pickup.) Getz is serviceable (and heroic at the end). Davis is beautiful and moving throughout. But the greatness of Jeff Goldblum is hard to describe or compare. Not for a moment does he hide beneath the make-up or technology. Unlike his character, he is a man to the end.

BrundleFly is what we have become, what we have been forced to become. On our way to becoming what Seth is at the very end: part-human, part-heartless insect (or should that be iNsect?), part-thing.

Be very afraid. . .

Friday, August 11, 2023

Tuesday, August 8, 2023

Friday, August 4, 2023

Wednesday, August 2, 2023

Wednesday, July 26, 2023

Communism!

Friday, July 21, 2023

Tuesday, July 18, 2023

Saturday, July 15, 2023

Revolt in Russia!

Tuesday, July 11, 2023

Friday, July 7, 2023

It Was You, Kazan

April 1952. Two weeks after the emotionally elephantine Streetcar Named Desire cops four Academy Awards (including Best Actress, Supporting Actress, and Supporting Actor), ex-Red-and-then-Hollywood big shot Elia Kazan, Streetcar's director, testifies before the House Un-American Activities Committee, naming eight former comrades as members of the Worldwide Communist Conspiracy, including Ed Bromberg, Paula Miller, and future snitch Clifford Odets. Eight names already known to HUAC.

Never one to avoid the spotlight, Kazan sends an unrequested letter to the New York Times days after his turning:

I believe that Communist activities confront the people of this country with an unprecedented and exceptionally tough problem. That is, how to protect ourselves from a dangerous and alien conspiracy and still keep the free, open, healthy way of life that gives us self-respect.In a memoir published in 1997, Kazan admits he took a "warrior pleasure at withstanding" his political enemies -- defined in the early-1950s as anyone more threatening than Ike or Dick Nixon. He explains the decision to snitch by embracing his years (1934 - 36) helping to create the legendary Group Theater in New York City, and how his beloved Communist Party put him "on trial" because he refused to move the Group in appropriately Stalinist directions. After all, Kazan's devotion was to Art for Art's Sake, not to making messages. . .

I believe that the American people can solve this problem wisely only if they have the facts about Communism. All the facts. Now, I believe that any American who is in possession of such facts has the obligation to make them known, either to the public or to the appropriate Government agency.

Whatever hysteria exists - and there is some, particularly in Hollywood - is inflamed by mystery, suspicion and secrecy. Hard and exact facts will cool it. The facts I have are sixteen years out of date, but they supply a small piece of background to the graver picture of Communism today. I have placed these facts before the House Committee on Un-American Activities without reserve and I now place them before the public and before my co-workers in motion pictures and in the theatre.

I joined the Communist Party late in the summer of 1934. I got out a year and a half later. I have no spy stories to tell, because I saw no spies. Nor did I understand, at that time, any opposition between American and Russian national interest. It was not even clear to me in 1936 that the American Communist Party was abjectly taking its orders from the Kremlin.

Firsthand experience of dictatorship and thought control [Kazan moved to the US, from Greece, when he was four years old] left me with an abiding hatred of these. It left me with an abiding hatred of Communist philosophy and methods and the conviction that these must be resisted always. It also left me with the passionate conviction that we must never let the Communists get away with the pretense that they stand for the very things which they kill in their own countries.

In 1954, Elia Kazan directed a highly awarded movie (eight Oscars this time, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Original Screenplay) whose entire existence depends on a defense of squealing. Written by Budd Schulberg of What Makes Sammy Run? fame (who should know since Schulberg also destroyed his Red friends by testifying before HUAC), the scenario is based on the true-life heroics of Anthony DiVincenzo, a whistle-blowing longshoreman who did testify before an actual waterfront commission and was ostracized for it. Even though Schulberg attended every day of DiVincenzo's commission testimony, Schulberg, Kazan, On the Waterfront producer Sam Spiegel and Columbia Pictures itself refused to acknowledge DiVincenzo's contribution. After a lawsuit lasting decades, the studio finally settled.

Young and somewhat punchy ex-prizefighter Terry Malloy is pressured by older brother Charlie (Rod Steiger) and Charlie's gangster union associates to lure friend Joey Doyle into a physical confrontation with union thugs -- thugs who immediately murder Doyle by throwing him off a high rooftop. Stunned, realizing Doyle was eliminated to keep him from talking to a waterfront commission investigating union corruption, Malloy's pulled in dangerous directions by the dead man's lovely young sister Edie (Eva Marie Saint) and by a crusading local priest (Karl Malden). After another longshoreman is murdered to maintain silence, Terry goes to Father Barry and confesses that it was he who "set up Joey Doyle for the knock-off." Now in love with Edie and pushed hard by the priest, Terry decides to testify but not before brother Charlie tries, and fails, to buy him off with a cushy new job -- a failure that leads to Charlie's death. Full of wrath, Malloy testifies, is shunned, beaten up, threatened with death -- yet he wins the girl and his testimony does seem to break the back of the criminal union.

On the Waterfront is an egg with the shell of ruthless (almost hysterical) ambition, a layer of sleazy justifications on the part of its twin-stoolies Kazan and Schulberg, a driving desire to please its contemporary Masters, particularly Columbia Pictures head Harry Cohn, the biggest pig in the trough. (Rumor had it Cohn once ordered Sammy Davis Jr.'s eye poked out for sleeping with Kim Novak, a Cohn favorite. Funny how Steiger would basically play Cohn in 1955's The Big Knife, written by Odets.)

Yet inside the shell is the yolk of a beautiful and tender heart. It may be the only great film ever made in service to social evil. (As Salt of the Earth, its 1954 bizarro Doppelganger, is a rotten movie in service to social good.) The shell, as we watch, cracks and falls away, leaving the exposed heart. Schulberg and Kazan's "Local 374" bears no relation to any union local known to man. Its cartoon "leadership," whose waterfront headquarters seems to be the same shack used by Widmark and Thelma Ritter in 1953's Pickup on South Street, is made up of mumbling meatballs who say things like "I'll top the bum off lovely." Local boss John Friendly (Lee J. Cobb) is never seen as a union official (negotiation, tactics, goals). His early economic explanation to Terry in the bar about his own source of power and payoff is nonsensical. Friendly is more of a 1940s gunsel whose only antagonism is directed toward his own workers. This is a center of labor corruption? The workers themselves are all whipped, passive, castrated, afraid to do or say anything; and they are put in their place by accents, vocabulary, dress, shabbiness, and dirt. (Kazan and Schulberg's class prejudice is stunning. Is this the 50s or the 30s?) No one talks about anything interesting. But for brother Charlie and Pop Doyle (John Hamilton), there are no families here. No small groups of friends. No clubs or associations. No American Legion posts or bowling teams. No fun or enthusiasm. Pigeons -- frozen, scared, alienated, and helpless.

Did America win the war or not? Early-50s Hoboken is presented as a place where some invading army marched through leaving devastation and despair in its wake. Did Schulberg and Kazan, covering themselves, understand their projected solutions? The Catholic church seems one of them, a church seen as wholly apart from social action (beyond private and public confession), embodied by Father Barry, played in full car-alarm mode by Malden. (His speech in the hole after K.O. Dugan's death makes the movie go splat.) All secular political action is denied, except through cooperation with witch hunts. (And through the love of a beautiful young woman.) The writer and director seem to have forgotten the neighborhood roots and networks of their own upbringings. There's no sense of corporation, company, owner. (The shot of "Mr. Big" watching commission hearings on television must've been a salve to someone's conscience.) The word MONEY is never mentioned. Here the manufacturing and spreading of communalist terror is marked. It is the 1930s turned upside down. Kazan and Schulberg identify completely with Terry (who seems to have no second thoughts): under threat of death, a man testifies against gangsters vs. Kazan/Schulberg -- men who sold out their friends and their pasts in service to McCarthyist tools. And so rewarded for it.

Important moments make no sense. Why is Charlie murdered? What has he done to endanger the local? Killing him would only guarantee, as it does, Terry's "ratting." (A theatrical and very moving device.) As is the ending. Friendly wants his men to start unloading the waiting dock shipments. And, after having Terry beaten up, the men do, with the mauled Terry leading the sheep around John Friendly, into the arms of a much more fearsome-looking character -- presumably the owner of the waiting cargo. Edie and the Father smile. "The End" The iron door shuts.

It feels intended as a triumph, of sorts. Did Kazan and Schulberg really look at this? Is it possibly an underground blast at 50s US capitalism, where the workers truly have no escape? No, it isn't. And in the time of John L. Lewis, A. Philip Randolph, James Carey, Cy Anderson, David McDonald, and the brothers Reuther, what a lie it would be. We really are supposed to feel that the Good Guys win in the end. Hence, the shell.

Kazan's behavioral genius is present throughout in other ways. The way Edie walks by herself along the railroad tracks on her way to Father Barry, and her search across the rooftop looking for Terry, to give him her dead brother's jacket. The tenderness Terry shows toward his birds and toward his young Golden Warrior followers. Terry's shy, heartbreaking way of moving when he's alone, as if not worthy of being among others. His look up to the night as he unknowingly sends Joey Doyle to his death. The sad, ripped coat he wears to his testimony. His attempt to warn K.O. Dugan before the hit. The heart-stopping hesitation as he at last sees his brother ("Hey, Terry! Your brother's down here. He wants to see ya. . ."), now crucified against a wall with bullet holes surrounding his heart. And there is Bernstein's beautiful, dirge-like score. And Boris Kaufman's liquid, enormously detailed photography -- beyond noir.

Or is it all Brando? (Perhaps it is, since Waterfront's quiet ardency is nowhere to be found in previous [or future] Kazan works.) Most things iconic do not deserve to be. Brando's Terry Malloy is not only worthy of its legend, but is probably the greatest lead male performance in US postwar cinema. Written and seemingly played as a dumb and tender animal, Brando's Malloy -- among many things -- contains within itself a subversive power deeply at odds with the movie's "point" -- a man who has suppressed his soul in a kind of mechanical despair, following orders and enduring all the rest. But the girl and the situation is releasing his soul from its bondage. And Brando gives us a promise that it may break free altogether, to have at last a time purely for its own joy.

"Salt of the Earth came out at the same time as On the Waterfront, which is a terrible movie. And On the Waterfront became a huge hit, because it was anti-union. See, On the Waterfront was part of a big campaign to destroy unions while pretending to be for Joe Sixpack. So On the Waterfront is about this Marlon Brando or somebody who stands up for the poor working man against the corrupt union boss. Okay, things like that exist, but that's not unions. I mean, sure, there are plenty of union bosses who are crooked, but nowhere near as many as CEOs who are crooked, or what have you. But since On the Waterfront combined that anti-union message with 'standing up for the poor working man,' it became a huge hit. On the other hand, Salt of the Earth, which was an authentic and I thought very well-done story about a strike and the people involved in it, that was just flat killed, I don't even think it was shown anywhere. I mean, you could see it at an art theater, I guess, but that was about it. I don't know what those of you who know something about film would think of it, but I thought it was a really outstanding film." -- Noam ChomskyUmmm, no. Presented by the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers, written by Michael Wilson (blacklisted), produced by Paul Jarrico (blacklisted), directed by Herbert Biberman (blacklisted), and starring the immortal Rosaura Revueltas and Juan Chacon, Salt of the Earth is a black-and-white cross between a 1970s identity politics screed by Norman Lear or Alan Alda and Ed Wood without the magic or mystery. There's really nothing good to say about it. It does matter after all, beyond one's sincerity and intended meaning, what one does with the camera, with the light, at the editing table, with the actors.

In a place called Zinc Town, New Mexico, close to the Mexican border, a miners strike breaks out over safety and sanitation issues, and over preference being given to "Anglo workers" (who are nowhere to be found). When the men are forced to end the walkout via a Taft-Hartley injunction (not explained by Salt), their wives (!) take over the picket line for them, while the men go back home and do the dishes. What this accomplishes is unclear. On the movie's own terms -- and on reality's own terms -- it is absurd. One thing it does accomplish is the "empowerment" of the women. Toward what end is also unclear, except for the obvious further misery of the poor husbands. Based on the actual 1951 strike against Empire Zinc, Salt was denounced on the floors of the US Senate and House, boycotted by the American Legion and its members, its financing was investigated by the FBI, film labs refused processing, union projectionists were ordered not to spool it, right-wing vigilantes fired gunshots at the set, low-flying aircraft buzzed noisily over it to prevent recording, and the lead actress was deported back to Mexico. Since the movie would convince nobody of nuthin' (except for the already convinced), one can only marvel at what must have been the diseased and cowardly dark heart of mid-50s USA -- at a time when the world truly was America's oyster.

It is embraced in some corners as a piece of Rossellinian neo-realism, a homeland version of the incomparable Europa '51 (one of the great political films). Bunkum. Most of the cast were union regulars involved in the actual Empire strike. Unfortunately, the regs can barely speak let alone "act." (Professionals such as Revueltas and Will Geer are just as poorly directed.) Most scenes revolve around pronouncements such as "The installment plan is the curse of the working man" and "Brother Boris here, of the International, will lead us to victory" and "You treat your wives the way the Anglo bosses treat you" and (my favorite) "Guns are not people -- people are people." Again, on Salt's own terms, it is not progressive. It does not argue for solidarity. There is no whiff of perhaps joining up with the no doubt equally aggrieved Anglo miners. The enemy remains undefined. And the righteous sisters show lots of awareness of their own rights but none toward the frustrations and helplessness of their striker husbands.

Let us compare two scenes from Waterfront and Salt, across two sections of each film. First, having a beer:

The bosses struggle to get their men back to work:

There are many great political films, as obvious in their message as is Salt: Europa '51, Even the Rain, Casualties of War, Weekend, October, Pigs and Battleships, Berlin Alexanderplatz, Crimson Gold, Good Men Good Women, To Sleep with Anger, Do the Right Thing, Los Olvidados, even Syriana. But all of them, to varying degree, go to that place where the heart touches the beyond. They all genuflect, for all their brave ideologies (and despite the communal nature of the movie-making process itself), before the Mystery: movies -- through the demands of isolation and selectivity -- are a deeply private, anti-communal art form.

Elia Kazan kneeled before his Masters; and before the Mystery. Salt does neither; and it is chum.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)