Jim Douglass, JFK and the Unspeakable:

One summer weekend in 1962 while out sailing with friends, Kennedy was asked what he thought of Seven Days in May, a best-selling novel that described a military takeover in the United States. JFK said he would read the book and did so that night. The next day Kennedy discussed with his friends the possibililty of their seeing such a coup in the U.S.

"It's possible. It could happen in this country, but the conditions would have to be just right. If, for example, the country had a young President, and he had a Bay of Pigs, there would be a certain uneasiness. Maybe the military would do a little criticizing behind his back, but this would be written off as the usual military dissatisfaction with civilian control. Then if there were another Bay of Pigs, the reaction of the country would be, 'Is he too young and inexperienced?' The military would almost feel it was their patriotic obligation to stand ready to preserve the integrity of the nation, and only God knows just what segment of democracy they would be defending if they overthrew the civilian establisment. Then, if there were a third Bay of Pigs, it could happen. But it won't happen on my watch."

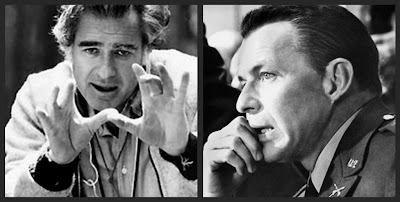

Director John Frankenheimer was encouraged by President Kennedy to film Seven Days in May "as a warning to the republic." Frankenheimer said, "The Pentagon didn't want it done. Kennedy said that when we wanted to shoot at the White House he would conveniently go to Hyannis Port that weekend."The Pentagon need not have worried.

Director John Frankenheimer did complete Fletcher Knebel's Seven Days in May (screenplay by Rod Serling) in the late summer of '63; and his views of the Kennedy White House during the final months of its life haunt the picture and give it an emotional and historical weight it does not deserve. The story is well-known. Air Force Commanding General -- and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff -- James Matoon Scott (Burt Lancaster) plans to overthrow the President of the United States (Fredric March in a manly, beautiful performance, his last starring role) -- a "criminally weak sister" who has just negotiated total and complete disarmament with the Soviet Union. Scott's executive assistant, a man named Jiggs (played in characteristically constipated style by Kirk Douglas), a man who has been cut out of the plot, stumbles across it, reports it to President Jordan Lyman, and after a number of twists and turns -- including the assassination of White House Chief of Staff Paul Gerard (a very effective and furtive Martin Balsam in a too-small role) -- the overthrow is suppressed, the plotters are forced to resign, all the happenings are kept from the childish U.S. public (something the movie endorses), and the Constitution of the United States is preserved.

Boy . . . does John Frankenheimer love the Constitution, and -- as we will see in the previous year's The Manchurian Candidate -- all the established institutions it "preserves and protects." Seven Days opens with the Constitution as backdrop, before giving us the director's vision of the political wars of the early 1960s: the John Birch Society/Minutemen/KKK vs. SANE/SNCC. A brawl breaks out before the gates of the White House. Not to worry. Here come the D.C. police in full riot gear to the rescue.

General Scott's plot is this: kidnap Lyman and hold him incommunicado while taking over all radio and television broadcasting by armed force; then announce on TV and radio the temporary but necessary suspension of civilian authority in order to prevent the military castration of the country. (Scott's plot would later be improved upon by Nixon/Kissinger/David Phillips/Pinochet in the 9/11/73 destruction of Chile.) What is to happen to Lyman? Is he to be assassinated along with other recalcitrant members of the Administration? (The Chief of Staff has just been killed to hide proof of the plot.) What is to be done with public resistance, even if it is merely of the NAACP/SANE/ACLU sort? Scott and the plotters have arranged for the takeover of electronic communications. What about the Washington Post or Time Magazine? ('Though Scott would certainly have had the full support of the Luces.)

Silliness aside, the movie does speak of something real. James Matoon Scott was mostly based on General Edwin Walker, the man stripped by President Kennedy for insubordination and the spreading of fascist propaganda to soldiers under his command. Resigning his rank, Walker in the autumn of '62 led the insurrection against the enrollment of James Meredith at the University of Mississippi, resulting in the deaths of two reporters. Attorney General Robert Kennedy issued a warrant for Walker's arrest on charges of sedition, insurrection, and rebellion. Walker's only response to the warrant, besides having it successfully quashed by a racist Mississippi judge, was to announce his candidacy for Governor of Texas (a race won by John Connally). Walker's last contribution to official history was to be the murder target of Lee Harvey Oswald seven months before Dallas, a Warren Commission canard thought ridiculous by General Walker himself.

Seven Days in May also speaks of how strongly John F. Kennedy had blown away the numbing Eisenhower fog of "cold war consensus" -- leaving him to face the fracturing of the culture formed by that fog and all the new power centers hidden within it, as he tried to guide the society into a quieter and more modest world, one more inward-looking and conscious-stricken. (Perhaps this was what his murderers hated most.)

The movie is beautifully told and paced, trim and clean (but for the bizarre detour taken on Ava Gardner's sad, slatternly performance, nicely introduced by Frankenheimer under "Stella by Starlight"). It also embodies the era's growing obsession with all things public and communal, as seen in its movies: Lilies of the Field, A Child is Waiting, Manchurian Candidate, The Best Man, Dr. Strangelove, Advise and Consent, Fail Safe, The Miracle Worker -- a time when the sight of fruit-salad, generals, admirals, and military bluster caused fear and loathing in the popular culture.

The scenes between Douglas as Jiggs and Ava Gardner -- all her screen time is with him -- are on a different track from everything else: they go nowhere. Gardner's deepening private heartbreak and her skill overcomes Frankenheimer's mere exploitation of her fading beauty and personal distractions (while Douglas just stands around). The movie wastes time on a cul-de-sac concerning compromising love letters written by the married General Scott (as if their exposure would somehow stop the coup) while eliding, beyond March's heartfelt loss over the death of his friend, the assassination of Chief of Staff Gerard. The intentional downing of Paul Gerard's airplane isn't even dealt with, it is merely presumed -- with no effect on future action. And after all, the love letters aren't even used. . .

There was a real-life Jiggs the whistleblower. His name was Abraham Bolden. Bolden was the first black Secret Service agent assigned to Presidential detail, and became a favorite of John F. Kennedy's. Because of complaints made regarding blatant racist treatment, and concerns expressed about sinister attitudes held toward JFK's safety by other WH agents, he was transferred to the Chicago S.S. office in early '62. In late October 1963, Bolden came across evidence of an assassination plot against Kennedy scheduled for November 2nd, during a motorcade from O'Hare Airport to the Army-Air Force football game at Soldier Field. Four men, four high-powered rifles, and a patsy -- working in a building overlooking the President's route. The potential patsy, Thomas Arthur Vallee (an ex-Marine loner with emotional problems), was picked up and held. Two of the snipers were also arrested, then released. The other two escaped the city. Kennedy's Chicago trip was cancelled as in 1963 the country seethed with plots: June '63, Beverly Wilshire Hotel (trip cancelled); November 2nd in Chicago; November 17th in Tampa (motorcade cancelled); Miami, November 19th (trip cancelled); Dallas on the 22nd.

After Kennedy's death, perplexed by the general embrace of the Lone Nut Theory, Abraham Bolden kept speaking to supervisors about the obvious connection between the local plot and what happened three weeks later, and repeatedly requested to testify before the Warren Commission about his Chicago evidence. On May 17, 1964, he directly called J. Lee Rankin, General Counsel to the Commission. On May 18th, Bolden was arrested and charged with fraud, obstruction of justice, and conspiracy, in connection with a black counterfeiting ring. In August 1964, he was convicted on all three counts. Abraham Bolden served three years and nine months in federal prison.

In focusing on a small group of cartoon conspirators vs. a small group of patriots, Seven Days in May ignores -- in the Year of Goldwater -- the rise of Western cowboy economies (space, oil, weapons, big agriculture), ignores the growing nationalist movements across the world, ignores the economic basis of the U.S. war machine, and ignores the ongoing wars within the American deep state itself. A coup launched for purely ideological reasons? Never.

But for a tender version of Iceman Cometh (1973, originally made-for-TV but given theatrical release) starring Lee Marvin, with final roles for Fredric March and the immortal Robert Ryan, Seven Days in May would be the last interesting feature Frankenheimer would make. Although his connection to political murder would carry on. He would host, at his Malibu home, Robert F. Kennedy on his last full night and morning, and drive the Senator to his Ambassador Hotel execution.

Frank Sinatra met John Frankenheimer at a 1960 Hollywood campaign party for Senator John F. Kennedy. Legend has it, Kennedy mentioned (between dances) a book he had just enjoyed, a best-selling political thriller by Richard Condon called The Manchurian Candidate.

The director's work prior to the party consisted of almost 200 (mainly social issue) television dramas. In 1960, godfathered by Burt Lancaster, Frankenheimer was given his first shot at a full-blown feature (a forgettable independent called The Young Stranger came-and-went in 1957): The Young Savages, starring Lancaster in a sort of black-and-white version of West Side Story without the songs. During Savages, Frankenheimer and producer George Axelrod (screenwriter of Breakfast at Tiffany's) bought the rights to the JFK-endorsed Condon novel, a project already rejected by several studios. In early '61, they grabbed the interest of Sinatra and the movie went into production one year later.

The Manchurian Candidate would not be the first instance Frank Sinatra dove into assassination waters. Toward the end of his tortured, hopeless husband-love for Ava Gardner, before his Hollywood-career saving Oscar for From Here to Eternity, he contracted to play in Lewis Allen's Suddenly (1954) -- an inert, pointless movie made twice interesting: it is a movie the Warren Commission claims was TV-viewed by Lee Harvey Oswald shortly before Dallas; and Sinatra's raw, almost-hysterical performance as an Army section-eight turned mob-hired presidential assassin.

If The Manchurian Candidate has too much politics (or not enough of the right sort), Suddenly has none. Johnny Baron (Sinatra) doesn't know who is paying him $500,000 to kill Ike. And doesn't care. (My money is on Nixon and the Dulles Bros.)

Johnny summarizes the story's POV:

BARON

One President dead,

another arrives.

What changes?

Nuthin'!

The great Sterling Hayden, fresh off Johnny Guitar, plays a small-town California sheriff and is totally wasted. The whole movie feels post-dubbed; and has a McCarthyesque love of police authority. Sinatra doesn't appear until 20 minutes into a 73-minute movie, but when he does he blows a hole in the screen. We are now used to seeing strung-out military-trained psychopaths performing blowback when returned to families and country, as movie characters. Hardly at all in the Fifties, and Sinatra's in Suddenly is the most frightening. (The way he yells "It didn't stop!") Career desperation or not, what other star in that time would have signed on to play such a repulsive character?

How Ava deepened his talent; and his soul. . .

Frankenheimer's style in The Manchurian Candidate is as baroque and wet as his style in Seven Days is flat and officious. Yet the two works have much in common: worship of a behaving military and its honor; a 6th-grade history book's presentation of how power works; a classical conservative's faith in how it should; embrace of all existing institutions (lone exception, MC's Republican Party, not exactly a career-breaker in 1962); media power absent; so, of course, is capitalism. The two movies' decapitation plots are like Potemkin villages. In Seven Days the cadre of generals exist apart from national and state law-enforcement, from international support, from banking or other financial hierarchies. The word "corporation" is not used in either film. The intelligence community does not exist. (Did James Angleton secretly bankroll Frankenheimer as means of distraction?) Manchurian Candidate's plot is a Bircher nightmare, only worse. Here even the most virulent of the far right are Sino-Soviet front men and women. When Angela Landsbury (great ~ Sinatra wanted Lucille Ball for the part!) reveals to her son Raymond Shaw (Laurence Harvey) the final piece of the plot, she announces her intention to betray her Communist sponsors. How? For what purpose? For whose benefit? Raymond's? We see no plans made for his escape after assassinating drip candidate Benjamin K. Arthur. She says she will create the most vicious and bitchiest police state of all time. Again, how? By a Russian/Chinese land invasion? (The Sino-Soviet split was already obvious by '62.) Then Frankenheimer blows the scene with that stupid mommie-kiss.

In the screenplay adaptation, it's clear Frankenheimer and Axelrod hoped to push the more mythomaniacal and (worse) Freudian aspects of the Condon novel to comic book levels. All hopes crushed by Frank Sinatra's brave, naked, deeply-wounded performance.

Inside the thick political shell of the movie there exists two worlds elsewhere: Josie (Leslie Parrish) and Raymond; Rosie (Janet Leigh) and Major Marco. Here the work's obsession with ideology and plots quiets and ends. And briefly, it embraces a Borzagian world apart from the power-saturated universe. Perhaps the strangest and most unsettling parts of Manchurian Candidate are the flashback sequences with Raymond and Josie, and her dad Senator Thomas Jordan (John McGiver, stealing every scene he's in). For Raymond and the father seem irremediably gay. Nowhere to be found in the Condon book, the gayness extends to Raymond's first boss (and domestic victim) Hobart Gaines and his very fruity bedroom, and to the star-chamber scenes in Korea. (Similar to the torture in Michael Cimino's reactionary and stupid The Deer Hunter, in MC the facts are turned upside-down. The U.S. military and its puppet SVN army used tiger-cages for torture. The U.S. government in the 1950s -- the movie is set in the 1954-56 period -- created brainwashed/torture/assassination victims via Allen Dulles-sponsored programs such as MK Ultra.) And let's not forget the Red Queen. . .

With Raymond Shaw, Frankenheimer and Axelrod have added to Norman Bates of two years before in creating a new American type: the sexually-frustrated loner whose only real orgasms are acts of violence. Shaw could be Bates with a Cambridge polish and an alive mother. It was just the beginning: Oswald, Speck, Ray, Sirhan, Bremer, Hinkley, Manson, Whitman. All ostensible loners, all with sinister intelligence connections.

Frankenheimer is so successful with the brief scenes of Rosie and Ben Marco he almost capsizes the film. (Perhaps the half-hour cut after disappointing previews contained much more of the couple.) They exist in a different movie. (Days of Wine and Roses or perhaps Axelrod's Breakfast at Tiffany's.) We only get a taste which leaves a serious question: What draws her to this clearly sick and broken man? Has Rosie been sent to cover Ben, as Eva Marie Saint covers Cary Grant in North by Northwest? And let's hear it for Janet Leigh, such a talented gal who was indispensable to some of the key works of her time: Candidate, The Naked Spur, Touch of Evil, Psycho.

The Manchurian Candidate was a box-office bomb and -- along with Suddenly -- removed from circulation after 11/22/63. Seven Days in May was scheduled for an early-December '63 release, postponed until the following February with the planned ad-campaign and nation-wide showings trashed. (It only opened in select theaters in select big cities. None in Texas.) It was also taken out of circulation until around the time of Watergate. Both films are in an honorable and classical tradition of liberal filmmaking as vanished as the Hollywood Palace. (The only modern equivalent I can think of is Clooney's Good Night, and Good Luck [2005], a fine chamber piece whose sole theme seems to be: people should treat each other decently.)

While Seven Days in May made its final pre-release adjustments, and The Manchurian Candidate disappeared after completing its theatrical run, David Atlee Phillips, Richard Helms, General Curtis Lemay, Admiral Arleigh Burke, Allen Dulles, Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge, Des FitzGerald, Tracy Barnes, Jim Angleton and others murdered John F. Kennedy. Two days later, his accused assassin was killed on national television. On Novermber 25, 1963, Kennedy was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. On the 26th, Frank Sinatra, George Axelrod, producers Howard Koch and Edward Lewis, Rod Serling, Burt Lancaster, and John Frankenheimer all went back to work.